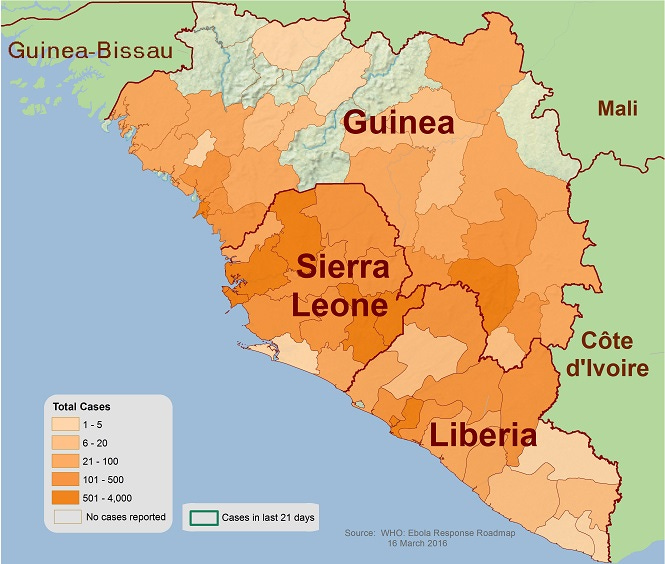

It’s the summer of 2014. Ebola has begun to spread through Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea. Western scientists have come to the rescue with a containment plan based on the latest and greatest medical science. Centralized hospitals have been constructed, aid workers have been dispatched to deliver safety protocols. A website called HealthMap pitched in to track the cell patterns of the infected and attempted to predict where the contagion might spread.

The western world was putting a considerable amount of resources and effort into the fight. But, as summer waned, Ebola continued to spread. The plan was going sideways, disturbing reports were emerging:

Patients were running away from hospitals

The sick were hiding from and even attacking healthcare workers

Funerals were held in which healthy people touched and kissed the infected corpses of Ebola victims

Medical advice and safety measures were ignored

By Autumn 2014, an average of ten attacks per month were occurring against medical and infection control teams

The CDC warned that the world was losing the fight against the disease and that more than one million could die unless something could be done.

Seeing through the Worm’s Eye

Amidst the chaos, a group of Antropoglists journeyed to Western Africa to see things through locals’ eyes. For weeks they tekked off-road trails to reach local communities, sending back their findings to offer a local Worm’s Eye View to balance scientists’ top-down perspective.

“I walked and walked and tried to listen,” recounted one researcher.

They saw firsthand why the containment efforts were failing. Medical experts were trying to distribute care and change behavior based on Western assumptions about culture. They hadn’t bothered to spend time on the ground to understand the local perspective.

“The perception of risk is a social process. Each culture is biased toward highlighting certain risks while downplaying others.” - Mary Douglas.

They found that even HealthMap’s tracking efforts were a bust. They were based on the assumption that each person owned their phone as we do in the West. In Western Africa, phones were shared and passed around, a community item vs. a personal one.

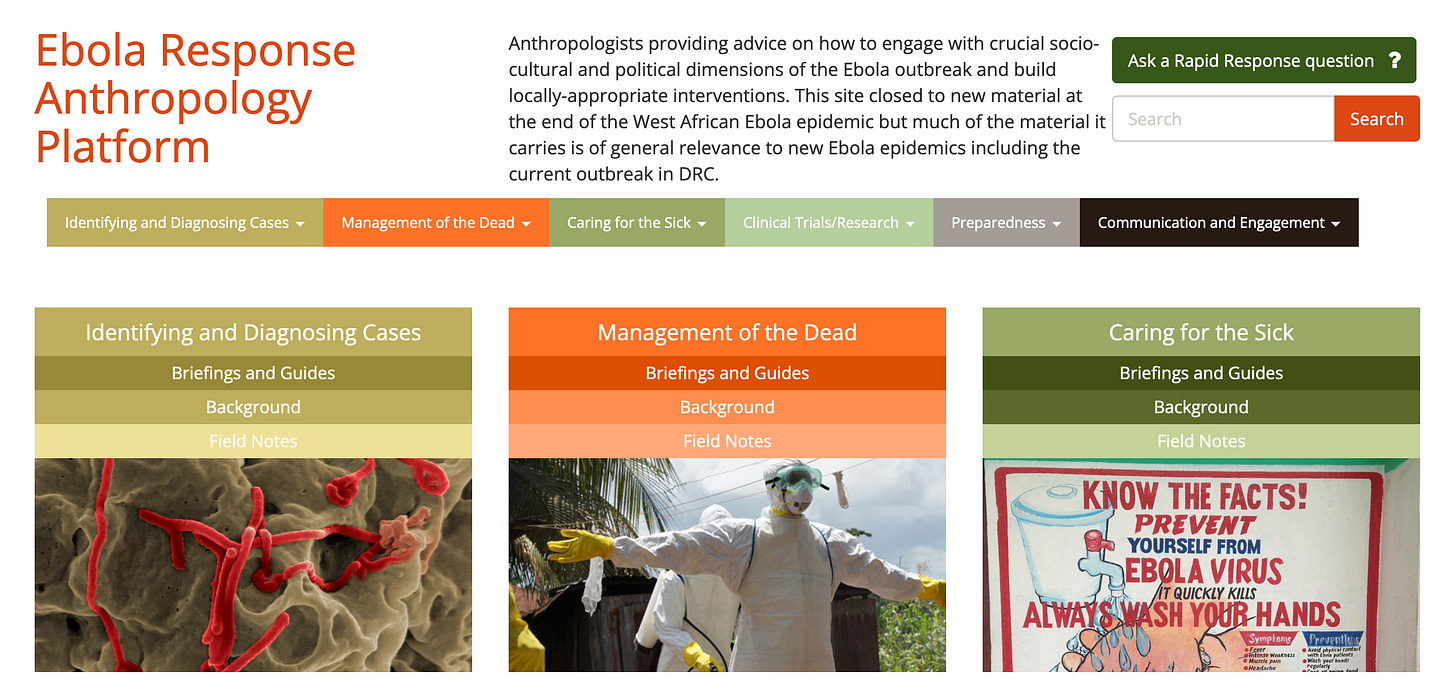

They published their findings and policy recommendations through a website, the Ebola Response Anthropology Platform, with the snarky tagline, “The objective of Ebola fighting measures is to combat a virus, not local customs.”

The Anthropologists policy recommendations would include measures that would ultimately turn the tide against Ebola.

Problem → They assumed the best way to contain the disease was to put the sick in in large, specialized ‘isolation centers.’ But the centers were far from the villages, the sick couldn’t travel more than a mile or two.

🪱 Worm’s Eye Solution → Build many smaller treatment centers near local communities. Also, make the walls transparent to reduce the fear and anxiety of the sick.

Problem → The advice to bury the dead quickly and without touching them was ignored. It ran counter to local beliefs - that the friends/family participate in a funeral with the body present else the deceased is consigned to a permanent hell. If healthcare workers buried a body without a funeral rite, locals would dig up the body to perform the ritual.

🪱 Worm’s Eye Solution → Devise funeral rites that are medically safe but meet the community's social and religious needs.

Problem → Medical advice from young outsiders were ignored. Locals only took advice from Village Elders.

🪱 Worm’s Eye Solution → Work with Village Elders to deliver messages about Ebola safety.

By the spring of 2015, communities were no longer digging up bodies, attacking medical staff, or running away from hospitals. By the summer of 2015, The World Health Organization declared victory - the outbreak was over.

Raveej Shaw, from the Whitehouse Ebola Response Team, recounted his learnings from the fiasco:

“We learned that you make policies much more effective when you work with communities and bring them into solutions.”

To which we might respond, OBVIOUSLY.

Yet how many of us are guilty of building products for a group of people without spending a day in their shoes?

Yes, this is a call out that you shouldn’t work through stakeholders who are removed from the situation on the ground.

I’ll paraphrase the product father, Marty Cagan - direct access to users is a requirement for product success.

I’m fond of saying that you should never work through proxies. You are accountable for the result, so you need to hear it from the source, from the users or customers.

Getting Wormy at Protector & Gamble

Many moons ago, Consumer Packaged Goods (CPG) giant P&G was trying to develop a new floor cleaner. Years of lab experiments yielded no results, they couldn't chemically create a better cleaning solution.

Perplexed, they hired industrial designers who went to consumers homes to see things from the Worm’s Eye.

They had two major findings:

Having a clean floor was super important, it was a central part of having a clean home.

Cleaing the floor sucked. Mopping was clunky, gross, and physically demanding.

The designers began to purposely spill coffee on the floor to see how people would clean it up. They would:

Grab a paper towel

Wet it

Bend down and clean up the spill

This became the inspiration for the… SWIFTER. A glorified wet paper towel at the end of a stick and all time CPG success story.

To build better products, spend more time with your users, and share their experiences. You’ll gain a nuanced understanding that will guide your decisions and unlock new options. Equipped with deeper insights, you can conjure up more original ideas.